This review is my attempt to convey the essential thoughts within the book as succinctly as possible, for my own reference and for those without time to read the whole thing.

Haidt is a man of many parts. He seems to be off to other pursuits since the publication of this book. One surprising consequence is that nowhere in the book does he offer a simple account of his five moral foundations. Or is it six? His point is mainly that they exist and that we in the west, especially liberals, are blind to all but care/harm and fairness/justice.

The bulk of the review consists of quotes from the book, indented and set off by purple stripes.

Introduction

Haidt’s title might as well have been “The Self-Righteous Mind. His objective is to get his readers to broaden their perspectives. He writes

I hope to have given you a new way to think about two of the most important, vexing, and divisive topics in human life: politics and religion. Etiquette books tell us not to discuss these topics in polite company, but I say go ahead. Politics and religion are both expressions of our underlying moral psychology, and an understanding of that psychology can help to bring people together.

I chose the title The Righteous Mind to convey the sense that human nature is not just intrinsically moral, it’s also intrinsically moralistic, critical, and judgmental.

If you think that moral reasoning is something we do to figure out the truth, you’ll be constantly frustrated by how foolish, biased, and illogical people become when they disagree with you. But if you think about moral reasoning as a skill we humans evolved to further our social agendas — to justify our own actions and to defend the teams we belong to — then things will make a lot more sense.

But human nature was also shaped as groups competed with other groups. As Darwin said long ago, the most cohesive and cooperative groups generally beat the groups of selfish individualists.

And I’ll use this perspective to explain why some people are conservative, others are liberal (or progressive), and still others become libertarians. People bind themselves into political teams that share moral narratives.

Haidt’s introduction to the book is as good of an introduction to this review as could have been imagined.

Part I: Intuitions Come First, Strategic Reasoning Second

1. Where Does Morality Come From?

Haidt’s first objective is to convince us of what morality is not. Despite what the Greeks, Kant and other may have thought, it is not the product of rational thought.

This is the essence of psychological rationalism: We grow into our rationality as caterpillars grow into butterflies. If the caterpillar eats enough leaves, it will (eventually) grow wings. And if the child gets enough experiences of turn taking, sharing, and playground justice, it will (eventually) become a moral creature, able to use its rational capacities to solve ever harder problems. Rationality is our nature, and good moral reasoning is the end point of development.

The rationalist approach emerged with modern liberalism in the WEIRD (Western Educated Industrialized Rich Demographies) nations. It was most enthusiastically advanced by Lawrence Kohlberg, building on Jean Piaget’s theories of child development. His student, Elliot Turiel, built on the notion that caring and harm prevention (alone) are the basis of morality.

Kohlberg’s timing was perfect. Just as the first wave of baby boomers was entering graduate school, he transformed moral psychology into a boomer - friendly ode to justice, and he gave them a tool to measure children’s progress toward the liberal ideal. For the next twenty - five years, from the 1970s through the 1990s, moral psychologists mostly just interviewed young people about moral dilemmas and analyzed their justifications. 11

They seem to grasp early on that rules that prevent harm are special, important, unalterable, and universal. And this realization, Turiel said, was the foundation of all moral development.

Haidt’s undergraduate readings of monographs in cultural anthropology convinced him there was more to the story.

I began to see the United States and Western Europe as extraordinary historical exceptions — new societies that had found a way to strip down and thin out the thick, all - encompassing moral orders that the anthropologists wrote about.

The WEIRD societies are uniquely individualistic.

Most societies have chosen the sociocentric answer, placing the needs of groups and institutions first, and subordinating the needs of individuals. In contrast, the individualistic answer places individuals at the center and makes society a servant of the individual.

The Western world reacted with horror to the evils perpetrated by the ultrasociocentric fascist and communist empires.

Haidt does not address the inherent contradiction in ultra-socialism being imposed on inherently, genetically as he will later argue, individualistic people.

2. The Intuitive Dog and Its Rational Tail

Darwin was a nativist about morality: he thought that natural selection gave us minds that were preloaded with moral emotions. But as the social sciences advanced in the twentieth century, their course was altered by two waves of moralism that turned nativism into a moral offense.

· The first was the horror among anthropologists and others at “social Darwinism” — the idea (raised but not endorsed by Darwin) that the richest and most successful nations, races, and individuals are the fittest.

· The second wave of moralism was the radical politics that washed over universities in America, Europe, and Latin America in the 1960s and 1970s. Radical reformers usually want to believe that human nature is a blank slate on which any utopian vision can be sketched.

The father of sociobiology, Harvard’s E.O.Wilson also thought there was more to morality than care and harm prevention.

Wilson sided with Hume. He charged that what moral philosophers were really doing was fabricating justifications after “consulting the emotive centers” of their own brains.

Supporting the thesis that there is a biological, psychological basis to morality, not mere rationality,

Antonio Damasio had noticed an unusual pattern of symptoms in patients who had suffered brain damage to a specific part of the brain — the ventromedial (i.e., bottom - middle) prefrontal cortex (abbreviated vmPFC); it’s the region just behind and above the bridge of the nose). Their emotionality dropped nearly to zero.

These synthesizers were assisted by the rebirth of sociobiology in 1992 under a new name — evolutionary psychology.

We do moral reasoning not to reconstruct the actual reasons why we ourselves came to a judgment; we reason to find the best possible reasons why somebody else ought to join us in our judgment.

contrast. His work helped me see that moral judgment is a cognitive process, as are all forms of judgment.

I read an extraordinary book that psychologists rarely mention: Patterns, Thinking, and Cognition, by Howard Margolis, a professor of public policy at the University of Chicago. Margolis was trying to understand why people’s beliefs about political issues are often so poorly connected to objective facts, and he hoped that cognitive science could solve the puzzle. Yet Margolis was turned off by the approaches to thinking that were prevalent in the 1980s, most of which used the metaphor of the mind as a computer.

From this Haidt concludes that

You’ll misunderstand moral reasoning if you think about it as something people do by themselves in order to figure out the truth.

3. Elephants Rule

IN SUM The first principle of moral psychology is Intuitions come first, strategic reasoning second. In support of this principle, I reviewed six areas of experimental research demonstrating that: Brains evaluate instantly and constantly (as Wundt and Zajonc said). Social and political judgments depend heavily on quick intuitive flashes (as Todorov and work with the IAT have shown). Our bodily states sometimes influence our moral judgments. Bad smells and tastes can make people more judgmental (as can anything that makes people think about purity and cleanliness). Psychopaths reason but don’t feel (and are severely deficient morally). Babies feel but don’t reason (and have the beginnings of morality). Affective reactions are in the right place at the right time in the brain (as shown by Damasio, Greene, and a wave of more recent studies).

4. Vote for Me (Here’s Why)

Early in The Republic, Glaucon (Plato’s brother) challenges Socrates to prove that justice itself—and not merely the reputation for justice—leads to happiness. Glaucon asks Socrates to imagine what would happen to a man who had the mythical ring of Gyges, a gold ring that makes its wearer invisible at will:

Now, no one, it seems, would be so incorruptible that he would stay on the path of justice or stay away from other people’s property, when he could take whatever he wanted from the marketplace with impunity, go into people’s houses and have sex with anyone he wished, kill or release from prison anyone he wished, and do all the other things that would make him like a god among humans. Rather his actions would be in no way different from those of an unjust person, and both would follow the same path.

Glaucon’s thought experiment implies that people are only virtuous because they fear the consequences of getting caught—especially the damage to their reputations. Glaucon says he will not be satisfied until Socrates can prove that a just man with a bad reputation is happier than an unjust man who is widely thought to be good.

I’ll praise Glaucon for the rest of the book as the guy who got it right — the guy who realized that the most important principle for designing an ethical society is to make sure that everyone’s reputation is on the line all the time, so that bad behavior will always bring bad consequences.

When nobody is answerable to anybody, when slackers and cheaters go unpunished, everything falls apart.

Tetlock concludes that conscious reasoning is carried out largely for the purpose of persuasion, rather than discovery. But Tetlock adds that we are also trying to persuade ourselves. We want to believe the things we are about to say to others.

The French cognitive scientists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber recently reviewed the vast research literature on motivated reasoning (in social psychology) and on the biases and errors of reasoning (in cognitive psychology).

They concluded that most of the bizarre and depressing research findings make perfect sense once you see reasoning as having evolved not to help us find truth but to help us engage in arguments, persuasion, and manipulation in the context of discussions with other people. As they put it, “skilled arguers … are not after the truth but after arguments supporting their views.”

Haidt appears in accord with the more realistic British moral thinkers like Burke.

It’s hard because the confirmation bias is a built - in feature (of an argumentative mind), not a bug that can be removed (from a platonic mind).

We should not expect individuals to produce good, open - minded, truth - seeking reasoning, particularly when self - interest or reputational concerns are in play. But if you put individuals together in the right way, such that some individuals can use their reasoning powers to disconfirm the claims of others, and all individuals feel some common bond or shared fate that allows them to interact civilly, you can create a group that ends up producing good reasoning as an emergent property of the social system.

The first principle of moral psychology is Intuitions come first, strategic reasoning second. To demonstrate the strategic functions of moral reasoning, I reviewed five areas of research showing that moral thinking is more like a politician searching for votes than a scientist searching for truth:

See more about Burke and Hume in the concluding sections.

In Part II I’ll get much more specific about what those intuitions are and where they came from. I’ll draw a map of moral space, and I’ll show why that map is usually more favorable to conservative politicians than to liberals.

Part II: There’s More to Morality than Harm and Fairness

5. Beyond WEIRD Morality

Haidt invented some hypothetical situations to determine people’s moral senses. One was, a guy bought a chicken, had sex with it, then cooked and ate it. Was that wrong?

Penn students were the most unusual of all twelve groups in my study. They were unique in their unwavering devotion to the “harm principle,” which John Stuart Mill had put forth in 1859: “The only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.”

But a few blocks west, this same question often led to long pauses and disbelieving stares. Those pauses and stares seemed to say, You mean you don’t know why it’s wrong to do that to a chicken? I have to explain this to you? What planet are you from?

If WEIRD and non-WEIRD people think differently and see the world differently, then it stands to reason that they’d have different moral concerns. If you see a world full of individuals, then you’ll want the morality of Kohlberg and Turiel — a morality that protects those individuals and their individual rights. You’ll emphasize concerns about harm and fairness. But if you live in a non - WEIRD society in which people are more likely to see relationships, contexts, groups, and institutions, then you won’t be so focused on protecting individuals. You’ll have a more sociocentric morality, which means (as Shweder described it back in chapter 1) that you place the needs of groups and institutions first, often ahead of the needs of individuals.

But as soon as you step outside of Western secular society, you hear people talking in two additional moral languages. The ethic of community is based on the idea that people are, first and foremost, members of larger entities such as families, teams, armies, companies, tribes, and nations.

The ethic of divinity lets us give voice to inchoate feelings of elevation and degradation — our sense of “higher” and “lower ” It gives us a way to condemn crass consumerism and mindless or trivialized sexuality. We can understand long - standing laments about the spiritual emptiness of a consumer society in which everyone’s mission is to satisfy their personal desires.

6. Taste Buds of the Righteous Mind

I was convinced that the prevailing view in anthropology was wrong, and that it would never be possible to understand morality without evolution. But Shweder had taught me to be careful about evolutionary explanations, which are sometimes reductionist (because they ignore the shared meanings that are the focus of cultural anthropology) and naively functionalist (because they are too quick to assume that every behavior evolved to serve a function).

It is ironic that nowhere in the book is there a succinct, satisfying presentation of the Five (or six) Moral Foundations: Care, Fairness, Loyalty, Purity/Sanctity, Authority and (optionally) Liberty.

The reader is best served by searching for them online. This is what this reviewer locates:

harm/care. We’re all mammals here, we all have a lot of neural and hormonal programming that makes us really bond with others, care for others, feel compassion for others, especially the weak and vulnerable. It gives us very strong feelings about those who cause harm.

fairness/reciprocity. There’s actually ambiguous evidence as to whether you find reciprocity in other animals, but the evidence for people could not be clearer. This Norman Rockwell painting is called “The Golden Rule” — as we heard from Karen Armstrong, it’s the foundation of many religions.

in-group/loyalty. You do find cooperative groups in the animal kingdom, but these groups are always either very small or they’re all siblings. It’s only among humans that you find very large groups of people who are able to cooperate and join together into groups, but in this case, groups that are united to fight other groups. This probably comes from our long history of tribal living, of tribal psychology. And this tribal psychology is so deeply pleasurable that even when we don’t have tribes, we go ahead and make them, because it’s fun. Sports is to war as pornography is to sex. We get to exercise some ancient drives.

authority/respect. Here you see submissive gestures from two members of very closely related species. But authority in humans is not so closely based on power and brutality as it is in other primates. It’s based on more voluntary deference and even elements of love, at times.

purity/sanctity. Purity is not just about suppressing female sexuality. It’s about any kind of ideology, any kind of idea that tells you that you can attain virtue by controlling what you do with your body and what you put into your body. And while the political right may moralize sex much more, the political left is doing a lot of it with food. Food is becoming extremely moralized nowadays. A lot of it is ideas about purity, about what you’re willing to touch or put into your body.

Part III: Morality Binds and Blinds

9. Why Are We So Groupish?

Our righteous minds were shaped by kin selection plus reciprocal altruism augmented by gossip and reputation management. That’s the message of nearly every book on the evolutionary origins of morality, and nothing I’ve said so far contradicts that message.

10. The Hive Switch

We are descended from earlier humans whose groupish minds helped them cohere, cooperate, and outcompete other groups.

That doesn’t mean that our ancestors were mindless or unconditional team players; it means they were selective. Under the right conditions, they were able to enter a mind - set of “one for all, all for one” in which they were truly working for the good of the group, and not just for their own advancement within the group.

Note

The mannerbund again. Tribesmen on the steppes

My hypothesis in this chapter is that human beings are conditional hive creatures. We have the ability (under special conditions) to transcend self-interest and lose ourselves (temporarily and ecstatically) in something larger than ourselves. That ability is what I’m calling the hive switch. The hive switch, I propose, is a group-related adaptation that can only be explained “by a theory of between-group selection,” as Williams said.4 It cannot be explained by selection at the individual level. (How would this strange ability help a person to outcompete his neighbors in the same group?) The hive switch is an adaptation for making groups more cohesive, and therefore more successful in competition with other groups.

11. Religion Is a Team Sport

The “hive mind” idea is present in Ricardo Duchesne’s “The Uniqueness of Western Civilization,” writing of the northern European männerbund, in which the Norse ability to fight as a group made them so formidable.

Haidt writes about the Greek pharynx and marching in modern armies.

But instead of talking about religions as parasitic memes evolving for their own benefit, Atran and Henrich suggest that religions are sets of cultural innovations that spread to the extent that they make groups more cohesive and cooperative. Atran and Henrich argue that the cultural evolution of religion has been driven largely by competition among groups. Groups that were able to put their by-product gods to some good use had an advantage over groups that failed to do so, and so their ideas (not their genes) spread. Groups with less effective religions didn’t necessarily get wiped out; often they just adopted the more effective variations. So it’s really the religions that evolved, not the people or their genes.

Haidt takes on the Four Horsemen of the New Atheism – Dawkins, Dennett, Harris and Hitchens.

Religion is costly, but those costs are more than recouped in group success.

Societies that forgo the exoskeleton of religion should reflect carefully on what will happen to them over several generations. We don’t really know, because the first atheistic societies have only emerged in Europe in the last few decades. They are the least efficient societies ever known at turning resources (of which they have a lot) into offspring (of which they have few).

Moral systems are interlocking sets of values, virtues, norms, practices, identities, institutions, technologies, and evolved psychological mechanisms that work together to suppress or regulate self - interest and make cooperative societies possible.

Turiel, in contrast, defined morality as being about “ justice, rights, and welfare. ”

12. Can’t We All Disagree More Constructively?

Here’s a simple definition of ideology: “ A set of beliefs about the proper order of society and how it can be achieved. ” And here’s the most basic of all ideological questions: Preserve the present order, or change it ?

Moral sense, and hence politics, is a heritable trait. Haidt cites twin studies to analyze the effects of heredity and environment.

Whether you end up on the right or the left of the political spectrum turns out to be just as heritable as most other traits: genetics explains between a third and a half of the variability among people on their political attitudes. Being raised in a liberal or conservative household accounts for much less.

After analyzing the DNA of 13,000 Australians, scientists recently found several genes that differed between liberals and conservatives. Most of them related to neurotransmitter functioning, particularly glutamate and serotonin, both of which are involved in the brain’s response to threat and fear.

[Jerry] Muller next distinguished conservatism from the counter-Enlightenment. It is true that most resistance to the Enlightenment can be said to have been conservative, by definition (i.e., clerics and aristocrats were trying to conserve the old order). But modern conservatism, Muller asserts, finds its origins within the main currents of Enlightenment thinking, when men such as David Hume and Edmund Burke tried to develop a reasoned, pragmatic, and essentially utilitarian critique of the Enlightenment project. Here’s the line that quite literally floored me:

What makes social and political arguments conservative as opposed to orthodox is that the critique of liberal or progressive arguments takes place on the enlightened grounds of the search for human happiness based on the use of reason.

As a lifelong liberal, I had assumed that conservatism = orthodoxy = religion = faith = rejection of science. It followed, therefore, that as an atheist and a scientist, I was obligated to be a liberal. But Muller asserted that modern conservatism is really about creating the best possible society, the one that brings about the greatest happiness given local circumstances. Could it be? Was there a kind of conservatism that could compete against liberalism in the court of social science? Might conservatives have a better formula to create a healthy, happy society?

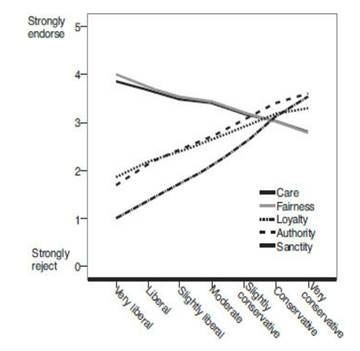

Haidt’s graphs show that conservatives tend to be guided by all five moral foundations, liberals primarily by care/harm and fairness/justice. He concludes that conservatives understand and can identify with liberals more easily than the other way around. Liberals, when asked to play the role of a conservative, emphasize narrow-mindedness, bigotry and hate. Conservatives see mainly naïveté and reluctance to deal with realities in liberals.

Thanks for your summary. I'm surprised he didn't mention human rights. Outside of the West nobody believes in it. Rights meaning privilege without obligation.

I think the actual division lies between individualists and collectivists, not liberals and conservatives. There are conservative collectivists - followers of evangelical religions are one example, the followers of Dugin's alt-right views another. Rural conservatives tend to be individualists as do conservatives from agrarian backgrounds, if from nothing more than their living conditions, in which social contact with others is much less than in an urban setting. Liberal individualists exist as well, from anarchists to (again) rural liberals - and then there are tons of groups who are liberal and collectivist. The social mores of each cohort of people - the rules b which they interact and share with each other in their particular identity are sometimes codified as moral codes, even laws - and sometimes left unspoken. I think that to some degree (more in some than in others) morals and the ideas of fairness and justice are inborn and can be oberved in very young children - and to some degree morals and the ideas of fairness and justice are instilled by parents and elders.I think some degree of self-consciousness, knowledge of individual agency, and empathy are the foundations for any sort of morality - some of these are inborn, others come from experience and the environment. There are people who are retarded or entirely lacking in some of these foundations - sociopaths and psychopaths lack empathy - and if this trait can be shown to run in families - even if children are taken away from the family group at an early age - it's possible that this is a genetic problem. Interesting article.